Give The Gift Of Play

One of the great pleasures of long, warm days is heading to the park after dinner. The kids think you’re the best for letting them get in an extra hour of play, while you think it’s the best that you get to cool it on a bench. But the playground is so much more than a fun way to tire out your tykes: Child-development research shows that it’s an important place they learn to challenge themselves, to cooperate, and to figure out what kinds of people they want to form relationships with— crucial experiences many children with disabilities miss out on because they don’t live near a playground equipped for their needs.

St. Louis mom Natalie Mackay, 40, has made it her mission to change that. Natalie’s oldest child, Zachary, was born with a rare nervous system disease that limits his ability to move. In 2001, looking to give the then 10-month-old some respite from nonstop doctors’ appointments, she decided to introduce him to the simple joy of being pushed in a swing:

“I put him in one of those infant bucket swings, and with one gentle push, his little body slumped over. It just about broke me. It felt like even the right to play was being taken from him.”

Then, in 2003, on a family trip to the East Coast, Natalie and Zachary visited a universally accessible playground meant to accommodate children of all abilities.

“There were ramps to the tops of the tallest slides and spaces that enabled him to play side by side with typically developing

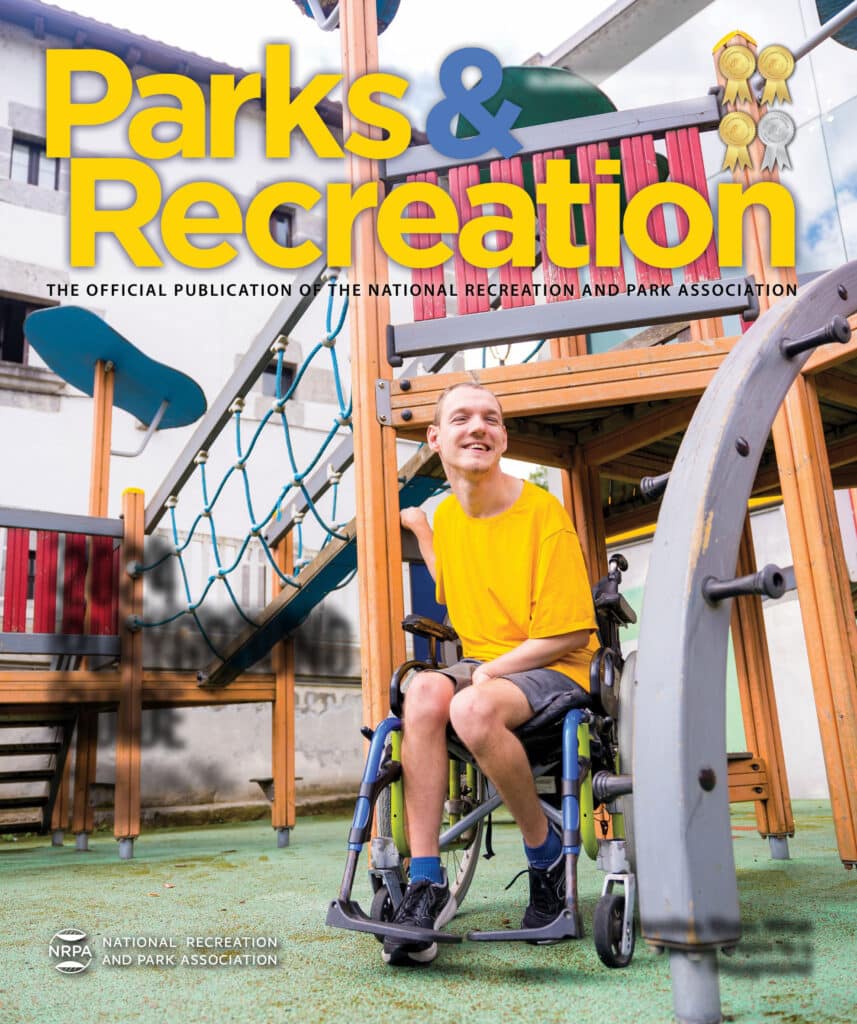

kids,” she says. “I remember when I was growing up, all the kids who were different were off in a different classroom in a different hallway. But a universally accessible playground would allow kids to actually get to know Zach. To me, it was hope that he wouldn’t just be ‘the little boy in the wheelchair’ to other kids.”

So Natalie—who, before becoming a full-time mom to three kids (now 17, 15, and 12), earned her undergrad degree in

recreation management—got to work: “I called five cities in our county and said, ‘If I handle all the fund-raising, would you allow me to build an inclusive playground?’”

Her nonprofit, Unlimited Play, has since opened 17 playgrounds in seven states, with at least 10 more on the way.

Missouri mom Kim Gibson watched in awe the first time her wheelchair-bound daughter, Gracie, hit one of the new universally accessible playgrounds:

“She happily said, ‘Go away; I don’t need you!’ With the playground’s special flooring, she could drive her chair alongside kids with mobility and do exactly what they were doing. It was inclusive for literally every child there. I just felt completely comfortable sitting down and watching her interact.” And that’s exactly as it should be. —Jessica Press